NFT technology facilitates the interaction with digital products. It also makes the virtual world more transparent and democratic in which digital creators gain direct access to consumers, bypassing institutions and national borders. However, the NFTs creators and buyers perceptions do not necessarily meet the legal reality. For those just getting into minting NFTs and looking to figure out how to market and advertise their NFTs, for those who aims to invest in these digital assets, both you are in the right place. This briefing will give you an initial insight into the NFT’s life cycle and the legal implications associated with their creation, marketplace transactions and ownership.

Evelyse Carvalho Ribas

Art and Crypto lawyer

Dual qualified lawyer - Brazil and Portugal - with practical experience in various jurisdictions

https://www.linkedin.com/in/evelyse-carvalho-ribas-53475325/?locale=en_US

NFTs – Digital Certificate, License of Use, Ownership

Suppose I make a digital painting. Because I am the one who made the painting, I own the copyright to it. I can sell the digital image, license it, copy and print and keep it within the real marketplace. But let’s assume that I decided to take it as a digital file, upload it onto anEthereum blockchain, and then sell it as an NFT on that blockchain. The acquirer signs over to me a certain amount of the Ether, and I sign over to that party the digital file, all on the cryptocurrency’s blockchain.

This simple transaction leads to several questions about the nature and value of an NFT:

- In what sense did I sell the digital file?

- Did the NFT buyer purchase only the token or the token plus the right to possess the (now unique) copyrighted digital work?

- What ownerships do NFTs confer to the acquirer?

- How does one determine the precise rights a given NFT grants the buyer over its underlying asset without reading the token’s code?

- Does the license also cover the right to create an NFT, or does the holder have to apply for another license to create tokens over the digital asset?

- What if I did it a second time? Would the second version of my original painting sell for less than the first time around?

- Would putting it up again devalue the version that the first acquirer bought?

- Is it the NFT or the digital painting itself that holds the value?

- While I decided to keep the copyright of my original digital painting, images of that original asset can be copied infinitely and viewed by anyone on the internet?

- Whether the NFT buyer can require me to take steps against someone who has created unauthorised versions of the underlying asset, and if that counterfeiter, in turn, made a counterfeit NFT, who would or could take action?

- Suppose the token is sold to a second, third party. Are the ownership rights of the initial holder wholly extinguished, or do NFTs create a hybrid of ownership rights?

The debate about ownership, the copyright trading infrastructure, the value of proliferating copies, is endless.

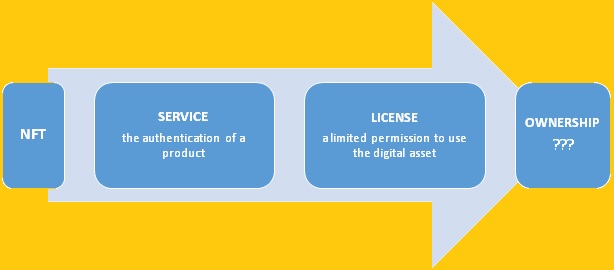

A fact is that most NFTs are providing a service or granting a license, but sporadic are the cases where the acquirer gets absolute ownership.

So, to answer those questions, we still need to understand what authentication, license and ownership of a digital asset are and how its value is formed.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Digital Certificate

Technically, when a collectable, an image, sound or text is attached to an NFT, the token proves that the digital copy of the underlying asset is an authentic copy of the original work. In this sense, the buyer of an NFT owns the token itself. When the NFT is transferred to someone else, the digital version of the work is transferred with it. Arguably, this creates factual control of the linked digital asset in a way similar to property rights.

Let’s look at a physical painting as a comparison. In this case, an NFT will function as a certificate of title or authenticity (or both) accompanying the tokenised painting rather than the painting itself.

Copyright protection exists independently from NFTs. In this sense, NFTs creators should be careful in marketing and advertising their NFTs; buyers of NFTs should understand what they are buying. Both perceptions do not necessarily meet the legal reality in different jurisdictions.

And to complicate it, blockchain verification does not necessarily eliminate the typical authenticity issues associated with physical products. NFTs can authenticate ownership of a token and the history of how such a token was developed and linked to a product.

However, an NFT alone cannot help match the creator of an NFT to a real person, nor does it validate that the creator of the NFT has the copyrights to tie that NFT to any specific digital asset. For example, an NFT may represent sculptor artworks and be sold as a creation of that artist, even though the sculptor had no role in its creation and did not authorise the use of images.

Some platforms use manual verification to solve the issue of counterfeited NFT artworks. For example, SuperRare and OpenSea require minters to submit information such as name, email, selection of artworks, social network presence, etc. Through this, the platforms aim to ensure that buyers receive authentic works from reputable authors who have appropriate rights in the underlying asset. Therefore, buyers should conduct the same level of authenticity and provenance diligence before buying an NFT that they would before buying a physical asset.

_______________________________________________________________________________

License to Use

When you buy a painting, a sculpture or a drawing, you buy only the physical artwork itself and not the copyright that would give you permission to make and sell copies or create new similar works. The same is true of NFTs, as no copyright is automatically acquired. In most NFT issuances to date, there has been a clear intention not to create ownership interests in the underlying assets.

When you buy an NFT, you are not purchasing the digital asset itself. You are purchasing a collection of code known as token, which links to the ‘true’ version of that digital asset. The token is written into the blockchain and contains information about where the original asset is located and who owns that particular version.

The scope of a purchaser’s usage rights for an NFT is determined by the conditions or licence terms of the applicable NFT, which will vary from token to token.

First, terms will determine if the intellectual property in the digital item remains with the creator or if the copyrights are passed to the buyer of the NFT. In this sense, creators should be mindful of the licence terms that any marketplace or platform offers to ensure they are not ceding more purchaser rights than expected. Buyers should be aware if they are acquiring only the token or the token plus the right to possess the unique copyrighted digital work. The scope of what is obtained, defined in a contract or a marketplace’s license to use, may state that others may still download, view, or listen to the work minted into the NFT.

Second, NFT’s buyers usually have limited permission to use and enjoy the digital asset: a fashion accessory, a painting, a piece of music, an audiobook, a video clip, a game character, a virtual land or a car. That means the creator of the NFT is keeping the copyright. By retaining the copyright in an underlying product, the creator of an NFT maintains the exclusive right to do certain acts concerning the asset restricted by copyright, namely the right to make additional copies, distribute, display or sell the product to someone else. In this case, marketplaces should warn that buyers do not have a copyright interest in the underlying asset and that creators of NFTs do not lose copyright protection over works when they are sold.

Third, some agreements only grant a license for personal, non-commercial use, while others allow commercial use of the underlying digital asset. The license to use may also state that the buyer cannot profit from using the underlying asset. Depending on the circumstances, the terms might also note that other versions, or editions, of the same NFT, can be sold.

The YellowHeart platform facilitated the sale of a new Kings of Leon album as an NFT. In short, the Terms of Service of the platform state that the NFT gives the buyer a right to display the album artwork, images and music files associated with the NFT. The right is only for personal use and lasts for as long as the buyer owns the NFT. The platform terms expressly exclude commercial activity related to artistic works behind the NFT, such as the use of related art or merchandise in third-party products or movies or other media.

Potential Claims

Each marketplace and product may have different terms. By checking them before a sale, the stakeholders know what involves their transaction.

It is becoming common that NFT buyers allege they misunderstood the extent to which they acquired rights when purchasing an NFT.

Others believe the scope of what they were receiving was not fully disclosed or was misrepresented, bringing claims for fraud or seeking rescission of the contract. Still, others get claims against the creator of the NFT for breach of contract because additional copies of an asset were sold, although the contract called for the work to have been a limited edition NFT.

To protect themselves, creators of NFTs and buyers interested in getting into the NFT market should familiarise themselves with the terms of what they are selling or purchasing and the scope of what will be transferred.

Both should also do as much due diligence as possible about the platform. It includes checking the Terms of Use.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Ownership

Traditionally, ownership is a simple legal concept that involves the right to enjoy and dispose of things in the most absolute manner. But the idea of owning an NFT on a blockchain is much more complicated than one might imagine.

Ownership of an NFT, demonstrated by an immutable digital ledger of transactions, means that the owner possesses the equivalent of a digital certificate of title or stamp of authenticity. This record of ownership can be found on the blockchain, while the digital asset itself is stored on a non-cryptographically separate server owned by a host platform (e.g. Opensea).

In practice, the NFT points to the separation between the NFT and the asset itself.

The buyer of an NFT owns the token that represents an asset. So, when the NFT is transferred to someone else, the underlying digital version of the work is transferred with it.

To illustrate the point, the purchasers of NBA Top Shot Moments have ownership in the NFTs, which means they can swap, sell or give their token away. The rights granted are set by the minter of the NFT (license to use).

Buyers, though, cannot exclude others from accessing the highlight clips. By holding an NFT, does not prevent anyone else from downloading and viewing the digital asset. In other words, a right to access or view something is different to owning rights in the represented asset.

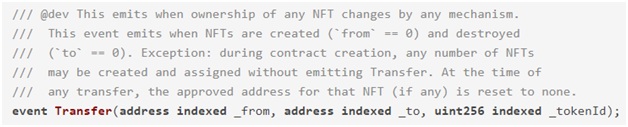

Some NFTs use the ERC-721 standard. This standard includes the following code comments about an NFT transfer event:

This code refers to “when ownership of any NFT changes,” but ownership of a token generally differs from ownership of a copyright. Certain digital assets have been recognised as qualifying as “property” (rights “in-rem”) in some jurisdictions. It remains open the question of whether the courts would recognise an NFT as proof of ownership to a digital version of the underlying asset.

Some advocate that holding an NFT creates factual control of the linked asset akin to property rights. The logic is that when an image, sound or text is attached to the NFT, the token certificates that the digital copy of the underlying asset is an authentic copy of the original work. However, as discussed above, the NFT does not necessarily transfer copyright, and therefore the scope of an NFT buyer’s enforcement rights is unclear.

Again, most NFTs do not claim to transfer any copyrights. Jurisdictions are taking steps to inform the public. The UK’s advertising regulator (Advertising Standards Authority), for example, in its April 2021 guidance on advertising NFTs, picked up on the importance of understanding the ownership:

“It is important to remember that the NFT is not the piece of art or image itself, but a method of tracking ownership. If somebody sells you an NFT for a digital file, that does not stop them from sending copies of that file to other people. The use of NFTs for copyright has also not been established, and therefore, owning an NFT does not mean that you own the copyright.”

Any party seeking to write or verify code for transferring copyrights should consult an attorney about compliance.

Once an asset is no longer protected by copyright, it falls into the “public domain”. Whether a work is in the public domain, you can use it freely without requesting the owner’s permission or even owning the piece’s copyright.

But when you mint an NFT, it must be your original work – keep it in mind. Note that, even if a piece enters the public domain, files such as images and sound may not be in the public domain if they were taken later.

Indeed, the digitisation and subsequent licensing of artworks by museums and galleries which hold them have been standard practice - though it is a topic not without controversy itself.

Nonetheless, the notion of an unconnected third party monetising such copies is a somewhat different scenario. It might look too flagrant an assault on the public domain to be considered acceptable. It might also violate contractual terms and conditions imposed by museums and galleries.

NFTs bring new digital pathways for individuals and enterprises into the global financial system. NFTs, cryptocurrencies and blockchains contribute to a new paradigm for digital authentication, license of use, ownership, secure data, value transmission, storage, and access. As such, the technological and economic particularities of NFTs require prudent regulation that accommodates the characteristics and use cases of the digital assets and the underlying blockchain technology.

Preview image: preview image and images in the text provided by the author

In most jurisdictions, the legislature and the judiciary have not yet had the opportunity to consider how the law would apply to particular scenarios.

It would be exaggerated to expect that the legislation – reactionary by nature – would answer all these complex, technical and legal questions in anticipation of the facts. So, this is an area that needs specialised legal services.