The Art Loss Register (ALR) is frequently the “first choice” in searching for lost, stolen and looted art, antiques and collectibles. Being the world’s largest private database, it currently lists 700,000+ items (in comparison, The Stolen Works of Art database of the Interpol lists 52,000+ items, see: https://www.interpol.int/en/Crimes/Cultural-heritage-crime/Stolen-Works-of-Art-Database). Information can be added to and searched for in this database on behalf of all the interested parties (both private and public), thus helping in performing the required due diligence, ensuring safety of the transactions and securing recovery of the lost/stolen objects for the claimant. The checks for the items stolen or lost in recent decades and during the Nazi era, amount to over 450,000 per year. Besides searching, the ALR team works on recovery and repatriation cases. Moreover, the ALR is managing the Cultural Heritage At Risk Database (CHARD). This database registers objects in situ at museums, warehouses and archaeological sites, ensuring their identification if stolen and offered for sale. To deeper understand the broad range of activities the ALR performs and the importance of its work for the art market practitioners, ArtLaw.club has had its honour to discuss the work of the ALR with its director Ms.Katya Hills and the team of experts:

The ALR is unusual in working with major players across the entirety of the art world. These include auction houses, dealers, museums, insurers, lenders, private collectors, artists and their estates so there is huge variety in the types of recoveries we complete.

We work on a global scale and see stolen items appear on the other side of the world to where they were stolen. For example, we recently returned a book to a library in Romania after it had been located at an auction house in the USA, over 4000 miles away. Additionally, we remind victims to never lose hope in recovering items, we frequently locate artworks stolen decades before. For example, last year the ALR returned seven gold snuff boxes to Temple Newsam, a historic house in Leeds, England. The boxes had been missing for more than 40 years! The ALR identified them following a request to research them from an auction house we work with and liaised with the insurer, museum and consignor over a number of months to facilitate a successful return.

This global view of the art market and the fact that an object could resurface at any time means that it is incredibly difficult to pinpoint trends in the types of objects being recovered. However, the key beneficiaries of our recovery work vary much less. Alongside helping private collectors, much of our recovery effort is on behalf of the insurance industry. If an object is insured and the insurer pays out, then recovering the item is an essential way for the industry to minimise its losses. For example, Henri Matisse’s ‘Petit Paysage du Midi’ was stolen in the 1980s from a London dealer. The work was insured, and the insurer paid out on a claim following the theft. The painting was missing for almost 30 years, until finally, it was spotted in an upcoming sale at a London auction house. The police were informed, the painting was withdrawn from sale and a settlement was negotiated with the sales proceeds split between the insurer and the consignor.

The charges of the Register are based on the net benefit of the registrants/clients. How is this benefit being calculated? Should there always be a pre-evaluation of the objects or the pre-known insurance value?

When we are working on recveries we work on a no win no fee basis. Once we locate an item for a client we charge a higher fee if they ask us to assist them on the recovery than we do if we simply let them know where it has appeared and they, the police, or their advisers, handle the matter from then on.

In both instances we make sure that our fee remains proportionate by charging a percentage of the benefit to them of the location or recovery. So if the recovery is unssuccesful there is no fee for the client to pay.

More details of these fees can be found on our website here: https://www.artloss.com/register/

When we are assisting law enforcement agencies or nation states who are the victims of theft or looting we offer our location and recovery services on a pro bono basis, and we also offer reduced recovery fees to museums.

The fees we charge for our due diligence work are fixed, and details of these can be found at www.artloss.com. It costs just 80 EUR to check a work with the ALR to ensure that you, or your client, can buy it with confidence. This drops to as little as 33 EUR per item if a bundle of search credits are purchased.

Is there any minimum value or standards (for instance, if the object is not unambiguously art object, but industrial one; or it is a bottle of wine or a rare old car) for the objects to be eligible for inclusion in the Register?

The crucial requirment to registeri an item on our database is that it must be uniquely identifiable. We must be able to tell it apart from other similar items or multiples on the market. Some items may be uniquely identifiable thanks to an edition/serial number, or distinctive markings such as damage or repairs, or a unique inscription. For this reason we do not register items such as fine wines and spirits, or most sneakers, unnumbered prints or generic jewellery. Typically, we only register items worth at least £1,000 as this is the threshold value we use for checking items at auction against our database. We find this works well because items below this value are much less likely to be unique and therefore it simply is not possible to be certain they are a match for the piece that is subject to a claim.

How do you follow the current status of the object? (for example, if the object has been registered with the Register, but later found/returned without immediately informing the Register)

Ideally the parties who report losses to us to inform us if they find the item again without any input from us. In any event, one of the first steps that we take when we locate an item registered on our database is to contact the party that reported it to us and ask them to confirm if it is still missing and if so whether they are interested in pursuing a recovery. If they confirm that the item has already been recovered in the meantime, then we quickly revert to the person who requested the search on the item and notify them that there is no longer a claim to it.

If a stolen/looted object has been found and successfully returned, do you keep the historical record that is publicly available?

It is important to clarify that none of our records are publicly available. Anyone wishing to check the status of an item must request a database search which our specialist team will perform. This means that we can maintain registrations confidentially, for example for those who do not wish to reveal that an item has been stolen in case it attracts more theives to their collection, or who have a security interest over an artwork that must be kept confidential under a contract.

We do keep a record on our database of all items that have ever been registered and their current status. Therefore, if an item has been recovered, we do not remove it from the database but instead we mark it as recovered. That means that if it ever pops up again in the market we will know that any issue that is raised, for example based on press reports from the time of a previous theft, has already been resolved and it does not need to be queried.

CHARD (Cultural Heritage at Risk Database) is a project that we began at the Art Loss Register specifically aimed at protecting cultural property in its country of origin. We proactively register items from sites, museums, galleries and collections that are at risk of destruction, looting or decay. These risks come from a number of different places, for example, from civil war, foreign invasions, climactic or environmental issues, or lack of adequate protection from theft. We register these items free of charge on our database. That means that the 450,000+ items that we check annually on the art market are searched against the CHARD database. If they appear for sale we know that they have likely been illicitly removed and we can get in touch with the cultural body that owns the pieces.

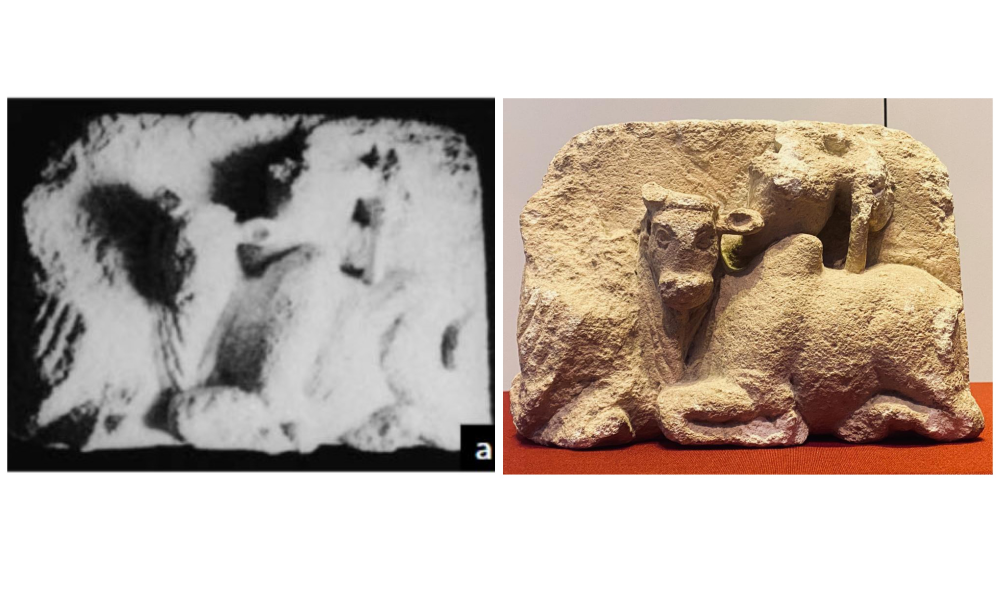

To give just one example of this in action, we registered the entire published catalogue of the National Museum of Afghanistan on CHARD. In November 2019 we identified a sculptural fragment being offered at auction in the UK which appeared in that catalogue. We contacted the auction house and the Metropolitan Police’s Art & Antiques Unit who secured the object for safe keeping. The National Museum of Afghanistan confirmed that this piece had been looted from their museum, likely in the 1990s and it was returned to Kabul..

This is an example of how CHARD can help in the repatriation of items that are not even known to be missing

We located a religious icon reported on the Interpol database by the Latvian authorities, which surfaced at a UK auction house. The item was the subject of a police investigation and had been stolen from a church in Latvia. The ALR liaised with the Latvian authorities via the Metropolitan Police’s Art & Antiques Unit, and helped to secure the item’s repatriation.

Did the Covid-19 pandemic and the recent geo-political situation affected the activity (searching for or registering new objects) of the Register? How would you evaluate it?

The nature and volume of thefts were impacted by the early lockdowns during the pandemic. We saw fewer house burglaries, street robberies and smash-and-grabs at jewellery stores or galleries, as more people were staying at home, busineses were closed and people no longer had occasions to wear their precious jewellery or watches out. Instead, as transactions moved online, so did thefts, and we saw a major increase in online frauds and scams, particularly in relation to luxury watches. The incidence of theft during shipment also increased, with goods intercepted or redirected while in transit.

With regards to the market, auction house sales quickly moved online and some auction houses created new specialist online-only sales which were very successful, particularly in the luxury goods sector. The online search engine for auctions and galleries Barnebys reported that watches and high-end handbags were among the top search terms among buyers on their platform in 2021. In general, auction houses with a global outreach fared well in the pandemic whereas those serving a local or national client base were more likely to see a drop in sales. For the ALR, this meant that overall we were checking fewer items on the market in 2020 compared to previous years, but the fine art and luxury goods markets bounced back quickly by the end of the year and in some cases even surpassed pre-pandemic levels so the overall difference was not that significant.

You are welcome to contact the Art Loss Register:

+44 207 841 5780

The preview images show the image of the sculptural fragment in the catalogue of the National Museum of Afghanistan and the recovered item following its location by the Art Loss Register in 2019. Both images courtesy: the Art Loss Register